Tuesday 15, February 2022

US yield curve

The world is worried about the yield curve. In a normal economy, long-dated rates carry an uncertainty premium. Lenders need a greater annualized compensation for locking up their money for a longer term. They bear a greater risk of inflation destroying the value of their savings. The expectation that short-term rates will have to be raised steeply has caused these rates to go up in anticipation. Longer term rates have moved up, but not by so much, hence the flattening. Nobody really knows what drives the demand for bonds. The world is, supposedly, suffering a ‘safe asset shortage,’ although I’d prefer to call it a collateral shortage. Foreign banks often have to get hold of dollars at short notice, so they use swap lines with the Fed. My understanding is that they pledge their holdings of bonds against the risk that the (FX) swap leaves the Fed with a loss. If the only acceptable form of collateral is a US T bill or bond, banks will choose the latter. The asset is treated as risk-free, in terms of banking regulation, and therefore doesn’t tie up any bank capital, and the long-dated bonds have decent running yields compared to the interest on excess reserves, albeit low ones.

Anyway, this model is going wrong. The curve is flattening, and this usually happens when investors foresee a recession, which collapses inflation expectations and what is happening to the curve spooks the central bankers. The big question is to what extent the prices (and hence yields) of long and short duration treasuries can be said to forecast anything in the economy, given that the Fed is manipulating rates across the maturity spectrum.

As I have said many times before, markets react to the expectations of the marginal buyer, not to the underlying macro economics. We may see long-dated bonds big hard if everyone becomes convinced that a recession is around the corner, especially if a war with Russia spikes energy prices and diverts real resources away from western economies.

Traditional risk-off assets are gold, Swiss francs, dollars, Japanese yen. I am unconvinced about any of these working as a hedge. The alternative is to short a risk-on asset, like the NDX. Don’t try this at home!

Oil futures

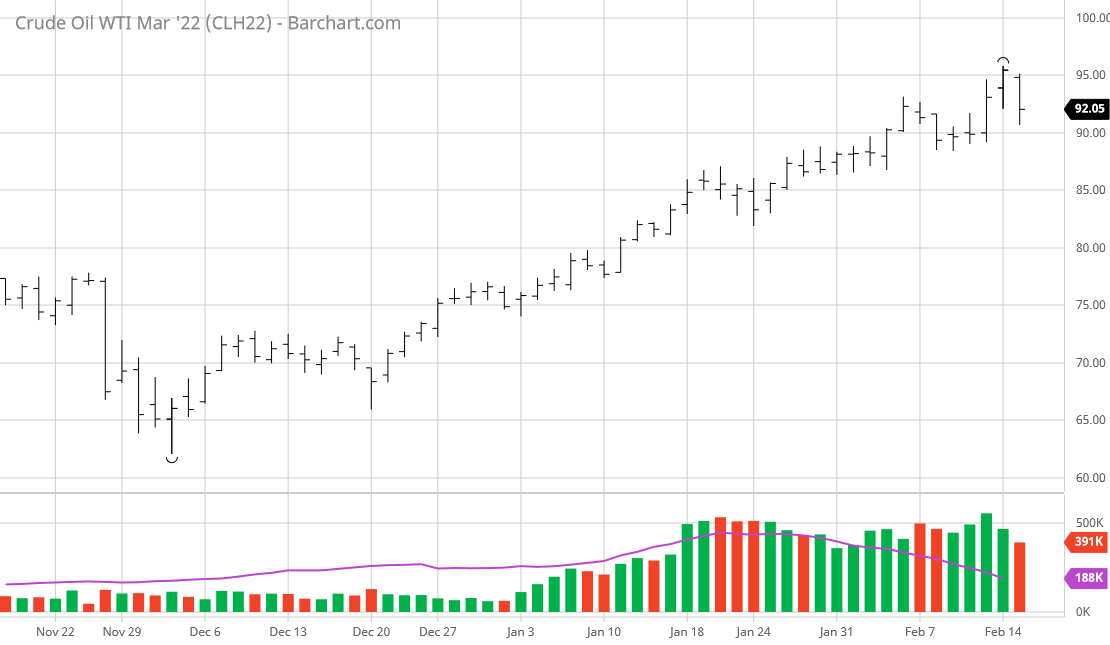

Interest rates for cash represent the cost of getting money now relative to the cost in the future. A 10% interest rate means that to persuade someone to lend you $100 today, you’ll have to commit to paying that person $110 in a year’s time. This is the normal situation. For oil, that’s not how it works, at least at the moment. To get a barrel of oil now, you’ll have to pay $95.46. Someone will allow you to collect a barrel of oil at the end of Feb next year for $81.70: about 15% less. This means that the ‘interest rate’ on oil is negative. In the jargon of the futures markets, oil is in backwardation.

This is usually explained in terms of a temporary bottleneck in supply (or spike of demand) now that is expected to fizzle out over time. Certainly, it indicates that oil is not buying into the inflation narrative.

Today the market decided that Russia was not going to invade Ukraine after all, and heaved a sigh of relief. Equity markets spiked up ($NDX up 2.4%), the dollar index sagged (95.99, down 0.38), as did soft commodities. The biggest change of all was a crash in the price of crude (near month future), which was down 4.9%.

With a mainly risk-on environment, a crash in oil seems baffling, but I guess it’s that the commodity is finally taking a pause after a very strong run for the last couple of weeks.

Comments !